Bob Gramsma, Riff, PD#18245, 2018 - Flevoland, Netherlands (July, 2024)

Background

This is the fourth post of five Land Art Flevoland sites that we visited in July, 2024. (I’ve repeated the next two paragraphs for all five posts)

Flevoland is the twelfth and newest province of the Netherlands. It exists in the Zuiderzee / Lake IJssel (a shallow bay connected to the North Sea, which they somehow converted from a body of saltwater into fresh water now), and almost the entirety of the province was added in mainly two separate land reclamation projects or polders. The first was in 1942 and the larger second started in 1955 and was completed in 1968. Flevopolder (as this new island was called) is the world’s largest artificial island at around 1,500 square kilometers.

Land Art was in its hayday of the 1960s and 1970s. In conjunction with the opening of this new land, the planners decided to add some land art pieces to become a part of Flevoland. Thematically it makes a ton of sense. Both creating Land Art and the empoldering process share a strong connection to the Earth and transformation of the landscape. You could even say that reclaiming this island was an even grander land art project. They’ve added 10 land art pieces now, with the most recent being completed in 2018.

Riff, PD#18245 was created by Bob Gramsma. It is hard to describe what it is, but essentially it is a concrete / soil fragmented monument with a flat top. Almost like an upside down mountain on stilts. It is both a sculpture and residual form. It is about 115 feet long, 39 feet wide, and 23 feet tall, weighing several hundred tons (it has not been accurately weighed). It has been described as a cross of a boat and a bridge.

The work, created in 2018, commemorates the centenary of the Zuiderzee Act of 1918, which contained three goals, protecting Central Netherlands from the North Sea, cultivate new agriculture to increase food supplies, and improve water management by creating a freshwater lake. This initiated the large-scale reclamation and transformation of the Zuiderzee into fertile polders and a freshwater lake. As we covered before, the island of Flevoland is one of these polders.

This artwork embodies the artificial and historical nature of the polder landscape by creating a physical imprint of its excavation process. Taking two years, it was constructed using unique techniques with assistance by WaltGalmarini (a civil engineering company out of Switzerland). 18 concrete piles were rammed into the ground. A steel structure was created in Gramsma’s design. While it’s one piece, there are three different sections that all are different heights (or depths I suppose). The project involved piling up soil from the region and created a hill on site. Then carving a large cavity within the mound to be the natural cast. Then poured in reinforced concrete mixed with remnants of Zuiderzee soil. The deepest (and first section goes 6-7 feet into the ground), the second, and third crevasses end where the existing concrete piles supported.

When it was dried and secured, the soil was removed, and what remained was an inverted, hollowed-out form resembling a vessel of geological history, balanced on a series of structural supports (with a hidden steel interior). A staircase (which was predesigned) was cleaned up, so visitors can ascend to take in views of the surrounding reclaimed land and its contrast with the old sea. There are some areas of it that are hollowed with gaps and access points for nature to purposefully take it over. The hope is that it will eventually be reclaimed, slowly with moss and insects, followed by more vegetation and animals. Thereby allowing the process of Riff, PD#18245 to continue..

This video is ideal to really see the process, which is key to understanding it, plus has great drone footage (the setting around it no longer looks like this). Also, it should be noted, since it has a strange name and I was wondering it, that PD stands for Public Domain, and #18245 is just the project number in Gramsma’s personal filing system.

Travel

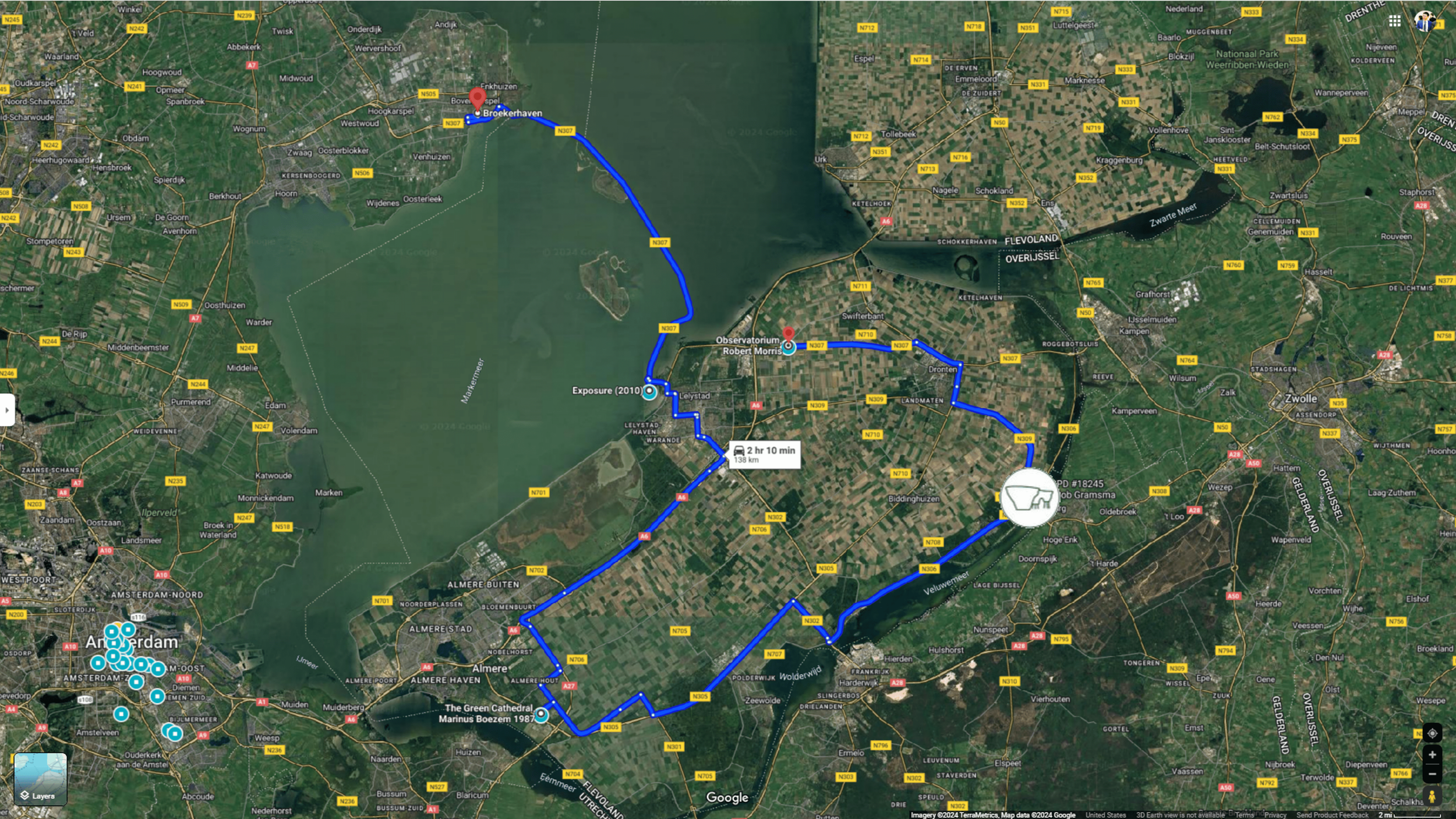

You’ll need to rent a car to visit, I don’t see a better way for you to get out there. It’s about an hour drive from Amsterdam.

You’ll see it on your right as you drive north on the N306 along the east coast of Flevoland. There is an easy turnoff and large parking lot to use. This address will help you get there via GPS (Bremerbergdijk 10, 8256 RD Biddinghuizen, Netherlands),but just typing in Riff, PD#18245 should work as well. The artwork sits below the parking lot, about 650 feet away. It is a flat paved road, that slopes into a relatively flat gravel dirt path. But it’s very accessible and should not be very difficult for anyone to visit. The staircase to the top of the structure isn’t though, it just has a hand rail.

It is free to visit and there are no hours of operation listed, though there are no lights, so I would stick to daylight hours. There is an informational plaque.

Restaurant Beachclub NU shares the parking lot, though it was closed the day we visited, so I have no information to share. There’s access to a beach called Spijkstrand which looked quiet and nice as well. There is a walking path along the coast called Bremerbergdijk / Spijkpad, if you fancy a stroll on an elevated path. There is also some strange amusement park called Walibi Holland down the street. I say strange only in that it’s European. I have no idea what actually is there or if it’s any good.

Experience

We arrived around 4:30 in a Monday afternoon (in July). There were only a handful of vehicles in the parking lot, and no one went to visit Riff, PD#18245, so we had it to ourselves. In typical Dutch fashion, there was a group of bikers preparing for a cycle. We parked and stretched our legs, walking down the slope to the artwork.

There is a plaque with some information by the entrance. It sits right alongside the N306, so there is a relatively steady stream of vehicles flying by. We beelined towards the stairs and climbed right up. There is a sign that obviously states that you shouldn’t cross the barrier at the top of the steps and walk along the top. There are no guardrails on the “roof”, and you could definitely fall off and gravely injure yourself. Or damage the concrete monument.

I’m sorry Land Art Flevoland. I hopped the barrier. It was too enticing and too flat to not wnat to walk on it. Plus there was broken glass up there. People clearly had been drinking on top and had gotten rowdy. I wasn’t the first, and I certainly won’t be the last to go up there. I have a healthy fear of heights, so I went nowhere near the edge. Mostly just sat on it and enjoyed the view and weather.

From the top I took the obligatory landscape photo. Notice my wariness of the edge. It is certainly a weird place to stand. That pond in the distance and other hills are all part of an effort to manufacture an ecology here to promote wildlife.

I took a seat on top while Mattos circled it and got some pictures.

It’s fascinating comparing it to images of it’s installation just a little over five years ago, and how much vegetation has grown up around it. It’s no longer just flat. It also didn’t occur to me at the time to go walk underneath the the shallower portion of the structure.

This is another one that would have been good to know more about the process and history before we had gotten there. Below is the official playlist for you to enjoy on your visit as well.

Summary

It’s worth sitting up top (and breaking the rules) and having a snack and a drink. It’s a weird otherworldy spot. It feels like an odd roadside attraction. The process of creating it is more interesting than it’s existence itself. Though the conceptual idea that this is a physical (raised) manifestation of the now defunct Zuiderzee is cool, but it does just feel like a strange roadside attraction.

Podcast / Interview

This is a link to Land Art Flevoland’s podcast / interview about Exposure. It is unfortunately in Dutch only. But I did put it through a transcriber (notta) and translator (Google). I apologize to the original content creators, I had to edit and bridge some gaps, but hey, I don’t speak Dutch, and I just wanted to share their content with more people. Hopefully they don’t mind. Below is the badly transcribed, translated to English, and edited interview transcript.

Luke Heezen: What happened here? You might wonder when you see the work Riff, PD#18245. In the middle of a piece of agricultural land, a kind of rock of 7 meters high rises up, somewhat bewilderingly. But it is an inverted rock. It starts off narrow at the ground and gets wider as you look up. The top is a flat plateau and there is a staircase that you can use to climb the mountain. It looks like the entire area around this inverted mountain has been excavated and only this little tuft remains. And that is exactly what happened. The construction of this work began in 2018 because it was 100 years ago that the Zuiderzee law came into effect. The law that made it possible for the Flevopolder to be constructed. Artist Bob Gramsma threw a huge mountain of 15 cubic meters of agricultural and Zuiderzee soil on one pile. He then dug an impressive pit in it and let a thin layer of concrete flow into it. When the concrete had hardened and a cast of the pit had been formed, he had the sand Elmeen removed. It is an artificial piece of landscape that is almost as cleverly manufactured as the Flevopolder itself.

I talk about it with Nils van Beek. He sits across from me and was involved in the creation of this work from his position within a team that initiates art in public space and develops and produces the assignment.

Nils welcome. [Thank you.] It is a very special work, difficult to write down too. Do you perhaps recall how the idea for this work came about?

Nils van Beek: Well, to start with, the work fits very well into the work of Bob Gramsma. So actually the method, the strategy that he has applied, he has done that in other works as well. He is, through his parents, originally Dutch, but he is a Swiss artist. And he also works a lot with forces of nature, and you have to imagine, in the mountains, avalanches that slide and that kind of thing. So that geological side plays a strong role there. And precisely because of thinking on that scale, it was a logical choice to ask him to do something here from his way of working. And what he finds particularly important is that the process also carries with it the meaning of the work. And that the process, indeed, as you said in your introduction, is a kind of duplication of what has already happened there. So if you can see an entire country as a kind of large landscape artwork, an artwork like Bob's helps to experience it that way.

Luke: Yes, so you stand there and then you think, oh yes, actually everything we see here was once made, reclaimed, excavated, indeed, that was created, or not created but that was created, yes exactly. And you are in the process light, what does that mean? That sounds very nice, but what does this mean?

Nils: With Bob, his starting point is really a sculptural principle. He says it's essentially about being in the world, what does it mean, that you take up space, that you move through space and how you can understand the space where you are. And he thinks that you bring that forward very clearly the moment you start making a hole. That is something he actually started with in his academy days, not already there. From the idea that we can relate uncertainly to our environment, but as soon as you make a hole, that is a space that we cannot understand. We can't really feel its dimension, we can't really understand its shape. And so, with a very large part of the space that surrounds us, we can’t really touch it..

Luke: Because it's a hole?

Nils: Yeah, it's actually amorphous. Bob has actually tried to make that somewhat amorphous space his material in his entire work. When you're making a model drawing, as an artist you have to have your eye-hand coordination, while you're looking at the model drawing hand already, and actually the skill that he's developed for himself is to be able to visualize in that way with space or immaterial space. So actually when he's going to make a hole, he really has a feeling of, yeah, what kind of shape is this actually and then I make it.

Luke: And you do that by casting it?

Nils: Yeah, then that shape is concretized all at once, so that we can suddenly grab it or understand it. And at the same time it also comes to life again a strange thing, and precisely that it is a bit strange, is therefore also consistent, that you just can't quite get it. And certainly in such a Flevopolder where everything is straight, then suddenly there is such an enormous, yes, more organic volume, which is also a strange entrant in our Dutch landscape.

Luke: It is a totally strange thing indeed and it is not just an inverted lump but it also has really strange shapes, how did they get there?

Nils: Yes, he really kept that image, so he made a kind of basic design, because it is such a large building, because that is what it is, of course it also needs a construction and in order to get a permit everything has to be completely thought out. But ultimately it is of course also about the skin of the work, so where the concrete comes against the wall of the hole, that is also what you ultimately see on the outside, such as the color and the stones and remains that are brought along and such, which are in the outside of the work. So when that basic shape was actually made, Bob really did with, literally with his hand, with the shovel, the real image of the shape, so also, here it has to be more, here it has to be less, and yes, he is also really able to do that, and that is exactly that part in the process that only he as an artist can do.

Luke: And that was also done with clay, right? The clay soil that is also characteristic here.

Nils: What is essential, look, because actually that mountain doesn't matter that much, except that it was created from the material that was lying there. So it really came from that large agricultural plot, he actually put that on a pile. So the composition of that is important for how the work ultimately becomes. But ultimately, and that is then also put back on the same terrain. But what was important for the composition of the soil, you have a layer of clay, and underneath that is also sand, that is the old sea clay. But you need that sea clay for the strength. So it had to be that exactly where the wall of the hole was, that there was a lot of clay, because you can really keep an image there. And if you just have loose sand, you can imagine that, that just falls, at a certain point, it is everywhere just like a dike, 45 degrees and flat. So for the shape you already needed that clay component in the soil.

Luke: That people know that it is not an ordinary mound of sand, it is really modeled with clay. And there is also a hole in it, I noticed when I walked around it.

Nils: In the work? Yes. It is also an important aspect, there are holes in it, Bob's intention is that the work is not placed on a pedestal like you would a sculpture, it is an object and that is it, as is actually the process, up to that form that is important, the process afterwards is also important. He says that actually that work is constantly changing. So to start with the idea that the area around it becomes new nature. And in that, actually in that new nature, that work also applies and those holes have been made, so that bats and other animals, I don't really know, but they can also take up residence in that work. And in that way the work also withdraws itself a little, just like, if you think, well, it's a bit of a strange form, and in that way too it withdraws itself a little from our order, so it simply gets its own natural life, it will also start to weather and that sort of thing. And I think that is also why it is important that you can get on it, and that it is very flat at the top, because it was not only conceived as a kind of lookout point, which also has a bit to do with the aspect of the 100 years of the Zuiderzee Act, but that you only really understand how that shape came about when you get to the top. Look, you can hear it in this podcast or read it somewhere, but in the experience it is very essential that you get on top of it, because then you see, oh yes, I am standing on top of a cast, actually. And well, there it is again very flat, and underneath that is actually that naturalness, so there you also come from that new nature reserve, yes, you actually rise above that a little bit. And that's why you also come up with these kinds of thoughts of, yes, who does nature belong to, we are actually part of it, but we pretend that we are going into nature, as if that is something that we can control, yes, and all those kinds of contrasts and paradoxes, that don't require the work of.

Luke: It is also a brave attempt to finally get a mountain in the Netherland, from a half Swiss of course. That is also interesting. What I also found beautiful is when you walk around it, then you see a kind of legs, kind of wooden legs.It almost looks like some kind of enlarged popsicle sticks.

Nils: Yes, what you see, actually, those are just the heaves. Look, Bob has chosen that the hole is of course really a hole, so that it also did not go all the way to the full depth of that bulldozer. So it just has shapes where it is sometimes deeper and sometimes less deep. But that is of course not something that can be freely woven, so that has to be supported. So there is a constructive side to it, but at the same time that concrete also behaves a bit like bronze, because yes, the concrete of the piles and the concrete of actually that shell, that of the sculpture itself, that also becomes a whole. Just like when you take a, say, bronze sculpture out of the mold that has just been cast, there are also all those air channels on it, because of course the bronze has also run in. In mold 1 you can also see that, let's say, part of the sculpture. And that's how it works a bit with Bob too. And I think that, yes, it's also, there's an association with a hot, but it's also important through these kinds of poles, that that reference builds on, yes, how we're used to doing that on our slacking base, for example. That is also stated there in the game brought. [?]

Luke: And artificiality too. Yeah. You keep remembering, oh yeah, wait a minute, this is not a real rock or a natural living material, this is artificial.

Nils: And I also think, look, if the whole thing were completely on the ground, then you would also relate to it differently, then you would not be able to walk under it. So also your legal experience of the work. And I think that is a very important starting point of the work. It is very different. That you can walk underneath and so on. So you also need that construction for that.

Luke: Yeah, we need to talk about that name. I can't pronounce it. Riff, PD#18245. Well, not really a classic title.

Nils: Riff of course has to do with something musical too, a kind of articulation in space and time, but also a coral reef where life can arise in and on. So that part is more poetic piece, but that code that is behind it, that is actually the code with which Bob indicates his works, so PD, that is to say public domain, and works that he has not made in a public context, for example an object for in an exhibition space, so that we have a different code.

Luke: So it's just his own system?

Nils: Yes, actually, but it's of course important that you also know from that, oh yes, it's part of a series of works, in a certain way of thinking, and I think that the experience of the work deepens even more, if you also see, oh yes, it's actually very consistent in the development of his whole life. It is not a single idea for this place, but actually his work brought into a new context, into the context of Flevoland.

Luke: That's a bit of homework then, for who we want to see it. Last question, how is the landscape in the immediate vicinity going to develop? Because that is in development.

Nils: Yes, it is a development. It was actually always the intention, also that we would look where there were different locations that would be suitable to conceive the work for. Incidentally, before the choice of the artist was made, but it was always the idea that new nature would arise. Well, look, agricultural land is always kept artificially dry. That will disappear, so it will become a kind of wet, puddle-like structure for a very large part. A lot of reed will develop and actually also at a certain point towards the forest edge a bit further on, increasingly higher, scrubby and a bit erratic bushes. A bit swampy. It won't be styled that much, although I don't think the final design has been decided yet. It's more like this percentage of water that these animals thrive on. So many percent of bushes where these birds can breed well again. That's actually what was thought about. But the idea is that you will be able to get to work via a kind of path or something, but otherwise it will be very wet and swampy.

Luke: So now we also have the opportunity to get to know the work in an environment that is actually going to change. So you can look at it in different stages. Certainly, yes, certainly.

Nils: Yes, you can actually see it change over the years.

Luke: Well, then we should definitely do that and then we can start looking at ice cream sticks, holes, on the plateau. A lot of the shapes of the Zuiderzee clay, so to speak, on the side. Learned a lot of new things, I think, to be able to look at that. Thank you Nils.

Nils: You’re welcome.

Sources

Provide Links throughout the article and aggregate at the bottom summary

Accommodations, attractions, restaurants, official site, additional readings

https://www.landartflevoland.nl/en/land-art/bob-gramsma-riff-pd-18245/

https://www.landartflevoland.nl/en/land-art/bob-gramsma-riff-pd-18245/more-about-this-artwork/

https://www.visitflevoland.nl/en/locaties/625712534/riff-pd-18245-bob-gramsma

https://sculpture-network.org/en/Magazin/LandArt-Flevoland-Niederlande

https://www.taak.me/en/activity/bob-gramsma-riff-pd18245/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7kwnBtVNOmQ